The Real AP: Valuing curiosity, not credits

November 3, 2015

I took my first AP (Advanced Placement) class junior year. Actually, I took four of them: Biology, Psychology, U.S. History, and Language and Composition (English III AP), and I was nervous. I didn’t know any of the kids in my classes. They’d all been AP and honors students since their freshmen placement exams, whereas I had only taken three honors classes my whole high school career. On day one, all my AP teachers told the class that usually there was one or two students who didn’t belong, that the individual would struggle, that things just wouldn’t click for them. And I was sure I was that kid in every case. However, as the class started up, I realized that many of my peers hadn’t done the summer assignments. Some of them didn’t even know that there were summer assignments. I tried; I studied for the tests, completed my homework most of the time, racked my brain for answers when others were silent. When I selected my junior courses I picked the ones I did because their content interested me and, having taking a college-level class that summer, for the stimulating atmosphere of an accelerated classroom. I was ready to debate, to inquire, and to grow, to become a more informed and intelligent individual, and to finally meet kids who cared more about the quality of the lessons than the grade they might make.

I asked several students, some enrolled in AP classes, some not, what they thought an “AP kid” was. Senior, Sarah Centeno, currently in AP Psych and Spanish V, believes AP kids to “actually be involved in the class, you don’t take it for the college credit, you take it because you want to or because you know you’re going to need it in college.” I can see, however, why some students’ main motivator to take an AP class is for the possibility of college credit. I embrace those kids, though I am not one of them, because they have motivation to do well in the class. My problem, and I believe this is Sarah’s issue as well, lies with the kids who use the college credit reasoning as an excuse because they really don’t know why they took the class. Or they do and it’s for less attractive answers like “all my friends are taking it” or “I’ve been in honors my whole life.” The reality is that there has been a jump in number of students taking AP classes to which the New York Times reports,“90% [of teachers] attributed it largely to ‘more students who want their college applications to look better,’” and only “32% to students who want to be challenged at a higher academic level” (Steinberg).

Senior, Klaudia Skladanowski, said she believes what makes an AP kid is the effort they put into their classwork: “They’re not smarter, they just work harder. They want to achieve something more.” Though I agree with her statements, as a seasoned AP student, I believe that even though we get assigned more work, it doesn’t mean we put the effort in. Whether it was in History or Psych, it was not uncommon for students to come to class, their binders full of blank pages, claiming they didn’t they know they needed to do the notes we were assigned every week since week one. But what should it matter? Most AP teachers rarely assign homework, and when they do, it’s often optional, like these notes. When the students aren’t familiar with the material nothing happens in class. Everyone sits there, dead-eyed, waiting for the teacher to give up and tell us what the answer to her question is. It was at moments like these where I wished AP kids were really all they’re chalked up to be.

School is duly dependent on a teacher’s willingness to teach and a student’s willingness to learn. They affect each other; if the students aren’t prepared to “play school” the teacher can’t feign a classroom, and vice versa. And when AP kids come to class, expecting their teacher to tell them everything they need to know, the benefits of higher-level classes become almost nonexistent. The College Board, creator of the AP program, defines AP as such: “a rigorous academic program built on the commitment, passion, and hard work of students and educators.” Now, I have my issues with the motivated-by-money company, but I digress. What the College Board claims to look for in students is the kind of people I thought I would be surrounded with. I thought everyone would be passionate and inquisitive, that we had opinions and ideas that we longed to share with others, but I just couldn’t find the right people.

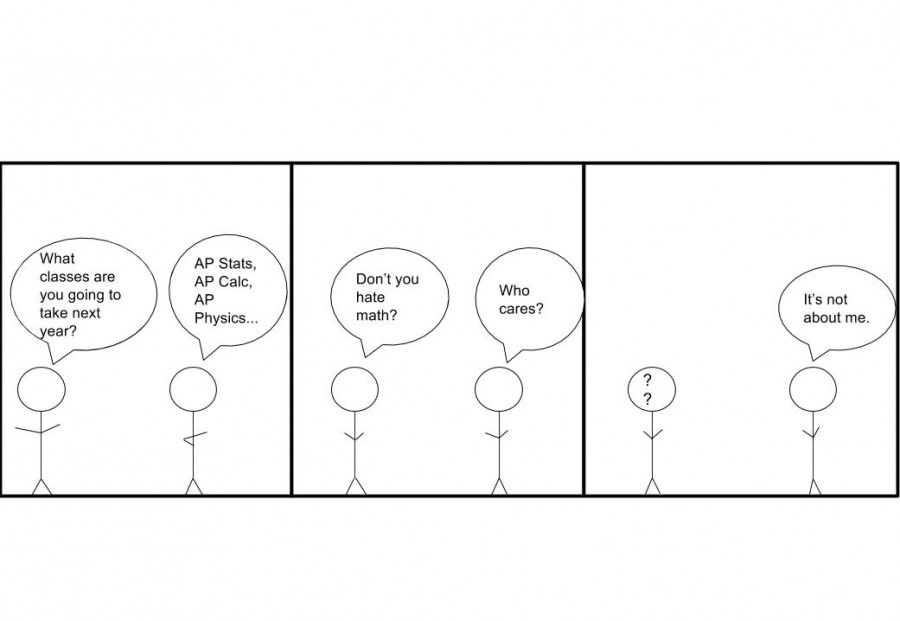

The idea of classes that make you think harder than you normally would, those were what I wanted to be apart of. And I think that’s how the Advanced Placement program began, with people remembering their childhood selves, confined to a textbook, told to stay within the pages. Even if this is not true, I still believe that’s what Leyden’s AP teachers want to give their students: an impassioned and and thought-provoking experience. This type of student, the kind with constant wide eyes, is going extinct. We’ve been taught to learn a certain way, to prepare for college, to put aside ourselves so that in the future we can be happy. We’ve forgotten how to question, how to think, how to wonder.

As AP students, as students in general, we should take a second and think about what we want. In order to bring the awe and amazement that enchanted us as children we need to find things that we love. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to be successful, but maybe the way isn’t through a bunch of classes that we don’t care about or even enjoy. Ask yourself now, so you won’t have to thirty years down the line, “What do I like to do? What is something I’ve always wanted to do?” And don’t waste your time trying to memorize cellular respiration unless it’s something you truly love.

Chris • Dec 1, 2015 at 12:36 pm

Taking AP classes for the purpose of getting college credit is a completely rational reason in my opinion. I took a total of 4 AP classes throughout my high school years and all were the sole purpose of getting college credit. The AP classes I took did not help me for my major nor will I ever use what I learned from those classes in real life. However, the credits I got from taking those classes and receiving a good score on the AP tests resulted in me getting 9 credit hours which is a good head start on college and it saved me money.